Space:-The new image was obtained using 16 telescopes at various locations on Earth that essentially created a planet-sized observational dish. The supermassive black hole pictured resides at the center of the relatively nearby galaxy, or M87, about 54 million light-years from Earth.

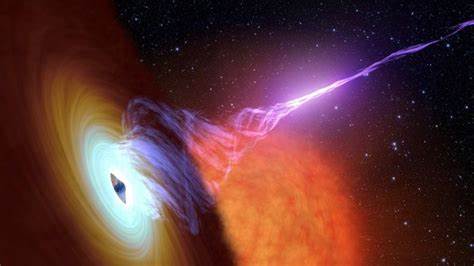

Washington: Expanding upon the historic first images of black holes, scientists on Wednesday unveiled the first picture showing the violent events unfolding around one of these ravenous cosmic behemoths, including the launching point of a colossal jet of high-energy particles shooting outward into space

Seeing the entire scene in the vicinity of a supermassive black hole can be insightful.

“This helps to better understand the complicated physics around black holes, how jets are launched and accelerated and how matter inflow into the black hole and matter outflow are related,” said astrophysicist and study co-author Thomas Krichbaum of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany.

Hard to observe by their very nature, black holes are celestial entities exerting gravitational pull so strong no matter or light can escape once caught in their grasp.

Most galaxies are built around supermassive black holes. Some are known not only to guzzle any surrounding material but also to unleash huge and blazingly bright jets of high-energy particles far into space – beyond the very galaxy from which they originate.

The entire system around a black hole is captured in the image for the first time. It shows the base of the jet of hot plasma, a fuzzy ring of light from hot plasma falling into the black hole, and a central dark area – sort of a donut hole – created by the black hole’s presence. Plasma – the fourth state of matter after solids, liquids and gases – is material so hot that some or all its atoms are split into high-energy subatomic particles.

“This is what astronomers and astrophysicists have been wanting to see for more than half a century,” said astrophysicist and study co-author Kazunori Akiyama of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack Observatory.

“This is the dawn of an exciting new era.” Lu, Krichbaum and Akiyama are members of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) project, an international collaboration begun in 2012 with the goal of directly observing a black hole’s immediate environment. A black hole’s event horizon is the point beyond which anything – stars, planets, gas, dust and all forms of electromagnetic radiation – gets swallowed into oblivion.

The EHT project has yielded the images of the two supermassive black holes. The second one – released last year – shows the one inhabiting the Milky Way’s center, called Sagittarius A, or Sgr A.

Those images, which showed just the darkness of the black hole and a ring of bright material plunging into it, and the new one all arise from observations using multiple radio telescopes worldwide. But the new one shows light emitted at a longer wavelength, expanding what can be seen.

“The image underlines for the first time the connection between the accretion flow (material pulled inward) near the central supermassive black hole and the origin of the jet,” said astrophysicist Ru-Sen Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

Those images, which showed just the darkness of the black hole and a ring of bright material plunging into it, and the new one all arise from observations using multiple radio telescopes worldwide. But the new one shows light emitted at a longer wavelength, expanding what can be seen.

Most galaxies are built around supermassive black holes. Some are known not only to guzzle any surrounding material but also to unleash huge and blazingly bright jets of high-energy particles far into space – beyond the very galaxy from which they originate.

Seeing the entire scene in the vicinity of a supermassive black hole can be insightful.

“This helps to better understand the complicated physics around black holes, how jets are launched and accelerated and how matter inflow into the black hole and matter outflow are related,” said astrophysicist and study co-author Thomas Krichbaum of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany.

“This is what astronomers and astrophysicists have been wanting to see for more than half a century,” said astrophysicist and study co-author Kazunori Akiyama of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack Observatory.